At a family reunion a few weeks ago, my aunt brought along a folder full of black-and-white photos from my grandma’s childhood in the 1930s and 40s. Grandma had what appeared to be a glamorous early life, as her family moved from New York to Buenos Aires for her father’s work in the telephone business.

I rifled through the photographs, stopping at one of my grandma at around the age of 12, holding a baby wrapped in a white blanket.

“Who is that?” I asked my aunt, pointing to the baby.

“Oh, that’s grandma’s little sister,” she said quietly. “Stella Maris. They named her after the boat they took to Argentina.”

As I stared at this baby I had never known existed, my aunt answered the question before I could ask.

“She died when she was seven months old. She had spina bifida.”

I had nothing to say but, “Oh, no.”

“And Grandma actually lost her first baby, too,” my aunt continued. “Before your dad, she had a stillborn little girl.”

At that moment, as a lump formed in my throat, my grandma walked up to the table and placed a hand gently on the back of my chair.

“Grandma,” I turned to her. “I’m so sorry.”

The picture of Stella was still in my hands. She looked down at it and smiled sadly.

“She looked so perfect when she was wrapped up like that. You would never guess about her spine,” she said.

“And I’m so sorry about your baby,” I added. “I didn’t know.”

Blinking back tears, she told me a terrible story: She hadn’t been awake for the birth—those were the days of “twilight sleep” deliveries. But when she came to, they told her she’d had a daughter that did not make it. My grandma named her Mary Frances.

“They asked if I wanted to see her, but I was still out of it, and they made me feel like I wasn’t supposed to say yes. So I didn’t.” She took a deep breath. “I know it would’ve been hard. But now, when I think about it, I wish I had held her.”

Again, words failed me. I wrapped her in a hug.

“People didn’t talk about those things back then,” she said simply.

These lost little girls have been on my mind for weeks, hovering just around the corner. It’s as if all the years of never knowing their stories compounded the weight of their absence, a boulder of pain now dropped at my feet. I keep thinking of my grandma, pressured to lock away her feelings, to move forward, chin up. It’s all wrong.

And then came this week, with the flooding here in Texas. News sites posting photos of precious gap-toothed grins, gone.

It is all too heavy. Too terrible. Too much.

What are we supposed to do with a world where little girls die?

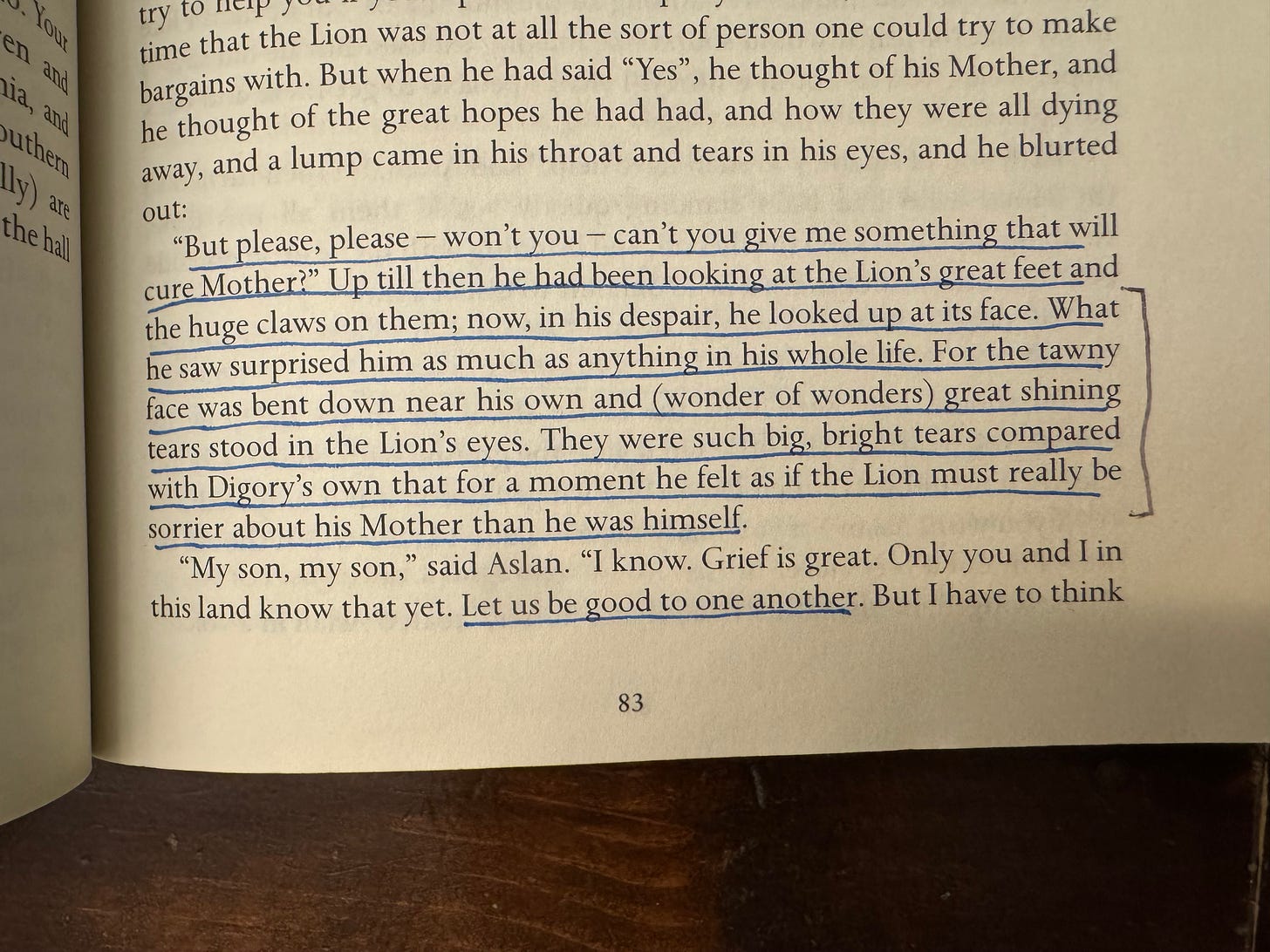

Earlier this week as I sat, refreshing the headlines, I shared a note with this quote from The Chronicles of Narnia and the bolded words below:

I have no easy answers, no tidy apologetic.

When there is a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes and the grief is great, I always come back to this passage from The Magician’s Nephew. My prayers over the last few days have been filled with please, please—won't you —can't you? It is hard to beg for mercy, then watch the death toll rise.

It doesn’t make sense right now for me to pray that a mother and father who can no longer hold their daughter would have “peace.” Hope? Yes, Lord, keep hope burning in their hearts. Rest? Yes, Lord, please help them sleep. But peace—in the sense of tranquility, or wholeness—that doesn’t seem like an option today.

Instead, I will pray that all those who are grieving losses too deep for words would scream and groan and cry—and see, through eyes filled with tears, that they are not alone in their pain. That they would feel the passion of a God who gets angry at death. That they would be surprised by the nearness and tenderness of a God who (wonder of wonders) weeps with us, with tears bigger than our own.

When I posted the note above, my friend

brought up the Old Testament mother, Rachel, weeping for her children. The image of Rachel weeping is first seen in Jeremiah 31, and Matthew includes her in his gospel when recounting how a power-hungry Herod ordered all the male babies in Bethlehem to be killed.“A voice was heard in Ramah,

weeping and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be comforted, because they are no more.” - Matthew 2:18

Abigail wrote: “I wish we practiced sackcloth and ashes and the loud mourning that taught people how to grieve. Our celebration of life services aren't cut out for this kind of tragedy.”

She’s right. While it seems we’ve moved forward from the days that forced my grandma to push down the feelings of losing her sister and her child, we are still a society embarrassed to lament.

Now, we expect parents to give a statement to CNN about the daughter they haven’t yet buried. The unspoken assumption seems to be: Stick to the script. Say she was a light, that she was loved. Don’t say it’s been hell. Keep things positive, grateful. Definitely don’t say, f*** you CNN, for daring to reach out to me right now at all.

Like Abigail said, we aren’t cut out for this. We need something deeper, something rawer, something more honest. We need to scream. We need to weep and wail and howl and groan.

We need to lament.

The American can-do spirit says we can take any tragedy and give it a positive spin. We are overcomers! A shallow, hollowed-out version of the Christian worldview takes our very real hope and distorts it, forming Jesus into a warped Uno-Skip-Card that we can slap over grief. No need to get too upset. God is good! All will be well.

But Scripture paints another picture: a mother who refuses to be comforted. Pages and pages of brokenhearted souls crying out, wailing, questioning. God in the flesh weeping at the death of his friend Lazarus in John 11.

But–shockingly and beautifully–it is not only sadness that Jesus expresses at his friend’s tomb. In his sermon given after 9/11, Tim Keller pointed out the following:

In verse 33, when Jesus saw Mary and the others weeping, it says, “He was deeply moved in spirit and troubled.” But the original Greek word means “to quake with rage.” In verse 38, as Jesus came to the tomb, it says he was “deeply moved.” The original Greek word there means “to roar or snort with anger like a lion or a bull.” So the best translation would be, “Bellowing with anger, he came to the tomb.” This must at least mean that his nostrils flared with fury. It may mean that he was actually yelling out in anger.1

When Lazarus died, Jesus did not send thoughts and prayers from afar. He did not tell his disciples they needed to make it to Bethany for the Celebration of Life, where they would smile and laugh and remember the good times with ol’ Laz.

Instead, he came to be with his beloved, brokenhearted friends, Mary and Martha. He came to weep with them. He came to rage against death, that horrible enemy.

And yes, he came to restore Lazarus to life. But not before feeling the grief, the anger, first.

Please do not misunderstand me. When I fight to make room for lament, I do not seek to diminish hope. When I confront death with bellowing anger, I am not forgetting resurrection.

Truly, truly I tell you that my only hope in life and death is that I am not my own but belong to God. I do believe, down to my toes, that all will be well.

And truly, truly I tell you that grief is great. It is right to cry. It is right to hate death.

I find comfort in knowing Jesus is a Man of Sorrows acquainted with grief. I find freedom in knowing that he hates death with a fierceness stronger than I could ever muster. I find hope, not in diminishing death as “nothing at all,”2 but in seeing that God hates this foe so much that he came to rob it of its power.

What do we do in a world where little girls die?

We groan and we beg God for mercy. We weep with those who weep.

In a culture that “averts its eyes from death and is embarrassed at every reminder of mortality,”3 losing someone is isolating.

I keep picturing the friends of these families who lost daughters. Friends whose families are whole. Friends who might feel like they couldn’t dare try to offer comfort to parents whose hearts are broken, while their own daughter is safe at home. But this is not the time to hide away from the hurting.

To lose a loved one is to be locked into a dark room. Those around you may wander in and hold your hand, but for them the door is always open, allowing a quick retreat when it all gets to be too much. You, however, are stuck, trapped, unable to leave. There is no reprieve.

When my mom died, my friends all wanted to be strong for me. They certainly meant well. But what I wanted was someone to walk into the darkness and cry beside me. I know some people were scared to tell me that they missed my mom—they thought it might be stupid, or hurtful, to say that to me, who certainly missed her more than they ever could. In reality, though, to hear that someone else felt her absence was an incredible gift. It showed me I did not have to carry the weight of grieving and remembering her alone.

So don’t hide your tears. Resist the urge to stay away. There are no perfect words that can make these things okay, so let that fear fall off your shoulders. The grieving do not need a sermon, but simple truths: I see you. I love you. I’m sorry. I’m here. They need eyes shining with tears like their own. They need to hear others bellowing in anger at the disaster, the rupture, the utter wrongness that has occurred. They need to know they are not alone.

Maybe you are feeling like me: angry and heartbroken that dozens of children in Texas will not grow up. Maybe you are feeling the weight of broken branches in your family tree, like Stella and Mary. Maybe you do not know what to do in a world where so much is so wrong.

It is not easy, and it is not tidy, but here’s what I will do—and here’s what I will pray that all the grieving will be able to do as the days of deep darkness drag on:

I will let the tears come. I will let the groans pass my lips. I will let the anger quicken my pulse. And I will look up into the Lion’s eyes, and hear him say, “I know.”

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/tim-kellers-sermon-9-11/

https://www.familyfriendpoems.com/poem/death-is-nothing-at-all-by-henry-scott-holland

From the beautiful introduction to Malcolm Guite’s collection of poetry on grief, Love, Remember.

Hannah, this brought me to tears many times. Especially how you close. "I will let the tears come. I will let the groans pass my lips. I will let the anger quicken my pulse. And I will look up into the Lion’s eyes, and hear him say, 'I know.'” As a former bootstrap-pulling optimist, I never knew what to do with the songs of lament. This picture of Jesus is so complete. Our hope of resurrection is sweeter when we have cried our bitter tears. I am saving this article to read again.